Part 1. The Russian art enigma

When I visited Russia a few years ago my conception of art was totally, naïvely, Western. I had not yet seen the wonders of Chinese or Japanese art, for instance, with their vast and limitless landscapes—even portrait tapestries where hues of mist dance about the trees and mountains—quite the opposite to the single, fixed viewpoint of the Western spectator. Russian art spans the realms of east and west and, as a product of its geography, boasts a unique and untamed view of people, ideas and landscapes.

In Moscow and St. Petersburg and Veliky Novgorod you will see icons of saints and the virgin adorned in gold; but for the most part, Russian art exhibits the mystery and exoticism of not only the East, but of the human condition within its social, political and natural environments.

‘That painting’

We all have ‘that painting’—a painting that on first glance you know will stay with you forever. At the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow I saw a painting that moved me; it was distressing, and yet, similar to when you first see Guernica or Pilgrimage to San Isidrio, I couldn’t bear to look away. The woman in the painting was vivid beyond anything I’d ever seen in the art world up until then. In Rome and Seville I have seen angels singing; in Madrid princesses dressed in finest silk; in London ambassadors at conference. And yes, while in Paris and Amsterdam and other places I have seen paintings of bloody battles and revolutions, depictions of the starving and biblical plagues, and still lifes that could pass for photographs—I had never seen anything so real as the furore and steadfastness in this woman’s face.

Vasily Surikov: Boyarina Morozova, 1887 (Source: russianicons.wordpress.com)

The faces of the people in the crowd are equally real, each with their own personality and look, whether of mischief or sympathy, hatred or horror. To understand the relevance of this painting is to understand Russia’s history. The woman in black is Feodora Mozorova—a once wealthy woman now fallen from grace because of her refusal to conform to new religious practices—being dragged to an underground prison where she will be starved to death. She makes with her hands the two-fingered blessing sign which is synonymous with the old faith and believers, who choose to uphold Russian church practices that differed from Greek Orthodoxy. But what I love most about this painting are the plethora of Eastern details—the religious headscarves, the traditional beards, the elaborately patterned dress—all accurately portraying the culture of Russia in what is in its composition a very European-looking painting by realist Vasily Surikov.

‘That artist’

Similar to ‘that painting’, we all have ‘that artist’—or like me, ‘those artists’ that inspire me. Mine include Tamara de Lempicka, Picasso, and David—to name but a few—but in Russia ‘that artist’, for me, is Natalia Goncharova.

What I love about Goncharova is the beguiling nature of her paintings. Her style boasts a primitivist and sometimes abstract portrayal of Russian folk life—most vividly in the colourful and flamboyant illustration of traditional Russian costume and dress that spans her works—enigmatic of the avant-garde.

This budding artist from Tula province—not someone who first comes to mind, like Chagall or Vrubel, when contemplating Russian painters—revolutionised Russian art in a way no one else has. Modernism, which was raging in Europe after the turn of the century, was the primary source of inspiration for her experimental design. As an adopter of cubism and futurism, she conceived rayonism—another ism etched in the history books!—and became a hugely provocative artist on the Moscow scene.

Rather than opt for one or the other, Goncharova took European influences and embedded them in the raw authenticity of Russian culture. During her first solo exhibition in Moscow in 1913, she claimed:

“I have passed through all that the West can offer at the present time, and all that my country has assimilated from the West. I now shake the dust from my feet and distance myself from the West.”

And the product? Not just intriguing works of art, but sensory experiences that elicit smells, sounds, and feeling to the beholder.

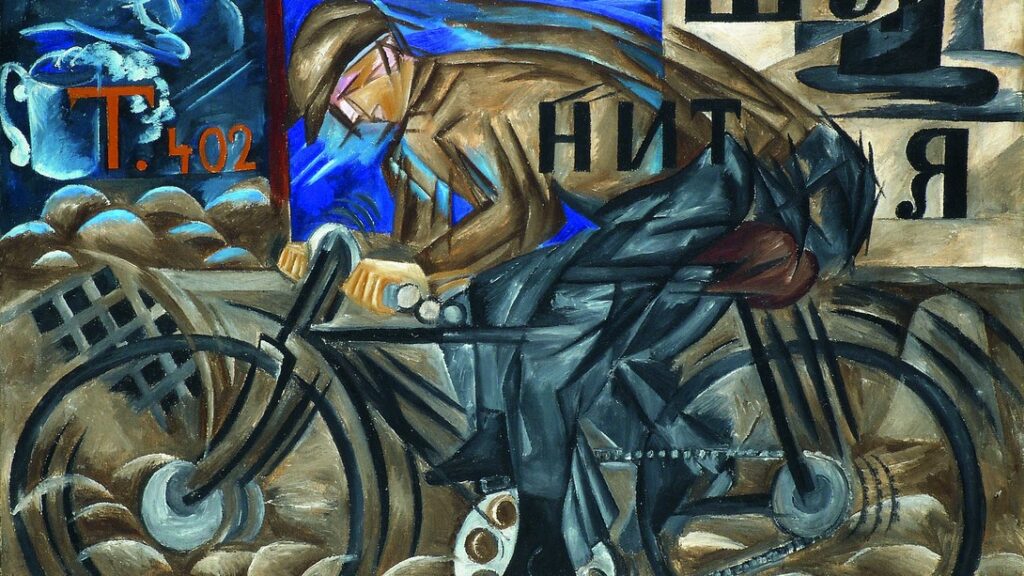

Natalia Gonchariva: Cyclist, 1913 (Source: wsimag.com)

Natalia Gonchariva: Self-Portrait with Yellow Lilies, 1907-1908 (Source: tate.org.uk)

Natalia Gonchariva: Peasant Woman from Tula Province, 1907-1908 (Source: tate.org.uk)

Part 2. Russia: a melting pot of sounds

Russian music has tussled between the West and the Orient for centuries. Take Russia’s most famous composer, Tchaikovsky. His music continues to captivate audiences all over the world—because like Vivaldi and Mozart it too adheres to the Western classical style. While you might be sat in the Hermitage, formally the Winter Palace, listening to the overture of Swan Lake, remember that your surroundings can be deceiving; because in fact the ballerinas are dancing to a German, not Russian, tale.

The Five, Rimsky-Korsakov and Scheherazade

‘The Five’, which included the likes of Balakriev, Rimsky-Korsakov and Borodin, worked together to revive the national style but struggled amid the growing popularity of Western classical music championed by the Petersburg intelligentsia. Again, years ago, I thought Tchaikovsky—since he himself was a Russian—a very Russian composer. But that wasn’t necessarily the case; while he did re-work some folklore melodies for modern tastes, he never ventured too far into orientalism and instead transcended the stereotypes of Russian music for a European audience.

Recently I listened to Scheherazade, the symphonic suite composed by Nicholai Rimsky-Korsakov, and it completely took my breath away. The mystical music dazzles and colours the mind with imagery of the Orient, close as anything to a journey along the Silk Road—across the Caucuses and due east. The Story of the Kalandar Prince and Festival in Baghdad are both, in particular, a work of magic. Perhaps the polar antonym of Swan Lake, Rimsky-Korsakov’s most famous work depicts the story of One Thousands and One Nights. The tale is deliciously enigmatic, centring around a Persian king—Shahryār—who upon learning of his wife’s infidelity kills her; proceeding to marry another woman the next day, and killing her too before she can dishonour him—assuming from his experience that all women are unfaithful. The music builds with fervour, telling the tale perfectly without words, as the Shahryār’s new bride, Scheherazade, tells him a story without finishing it—forcing the curious king’s hand to postpone the customary execution. And once she finishes her story the next evening, Scheherazade starts another unfinished tale—and so it continues until after one-thousand-and-one nights the Shahryār has finally fallen in love with Scheherazade. The beauty of Korsakov’s work lies in his ability to intertwine those rhythmic nuances of the middle- and far-eastern parts of the Russian Empire, into a harmonic symphony of music that is undoubtably reminiscent of those distant lands.

Ahy luli luli luli

While Russia’s art music takes inspiration from folklore melodies—like Borodin’s Prince Igor—its traditional music is embedded in the tales and legends of the ethnic groups living in Russia. If a Tolstoy novel could speak it would say, “Ahy luli luli luli”; a very authentic Russian sound which features in many folk songs that often follow village life, traditions and rituals. The music isn’t academic in style, it’s simplistic—bringing to life mundane yet beautiful moments like the first autumn snow, prayers at church or the harvesting of crops—and as such not usually performed by musical professionals but rather everyday people. The traditional song Little Birch Tree epitomises the core characteristics of folk style; birch or ‘beriozka’, an important symbol in Russian culture, means spring, light and beauty. Ancient Russians (Slavs) believed that birches had special spirits that would protect them and so planted the trees around their villages. This specific melody occurs in Tchaikovsky’s 4th symphony where he skilfully uses it at the beginning and then throughout the movement with different dynamics and embellishments. Half a century later the Soviets—who revived many traditional songs like the beriozka—considered Tchaikovsky’s kind of art music too ‘bourgeois’, because of its predominantly Western style. They preferred the more traditional and ‘proletarian’ folklore music, as it had closer ties to the idea of Mother Russia. Well into the dying days of the communist regime the state endowed traditional Russian music with financial support, claiming it to be the antithesis of Western pop music.

History repeating itself

In a wider context Russia has a history of brushing over its Eastern heritage in favour of more reliable, fashionable and sophisticated Western customs. There was Peter the Great who, having travelled much of Europe before becoming Emperor, built the very European city of St. Petersburg—the ‘burg’ lifted from German—Russia’s new imperial capital. He even created a ‘beard tax’ to enforce the ban on beards; facial hair was not de mode in court, but still revered among many classes of Russian men. Likewise, other tsars and tsarinas, such as Elizabeth and Catherine the Great, avoided provincial Moscow like the plague, preferring the more lavish and comfortable St. Petersburg. Successive emperors would continue to subjugate Russian civilization so much so that the court and high society became engrossed with French culture; up until and indeed after the battle of Borodino, where Napoleon conquered Russia’s sacred capital Moscow. It comes as no surprise that this custom of Europeanisation should dilute the native Asian foundations of art and music—since their existence and prosperity depended on both state and sovereign. And while the Soviets tried their best to supress cultural ties to the West, there’s no doubt that the Russian arts are a perfect blend of two halves.