I moved to London in the summer of 2012. Wide-eyed and eager to explore, this wasn’t the first time that I had been to the capital, but it was the first time that the city felt a little more like “my own”.

I was about to commence a postgraduate degree at UCL and consequently found myself with spare time on my hands. I am a prolific wanderer and in no time I was wandering in the direction of the city’s galleries and museums.

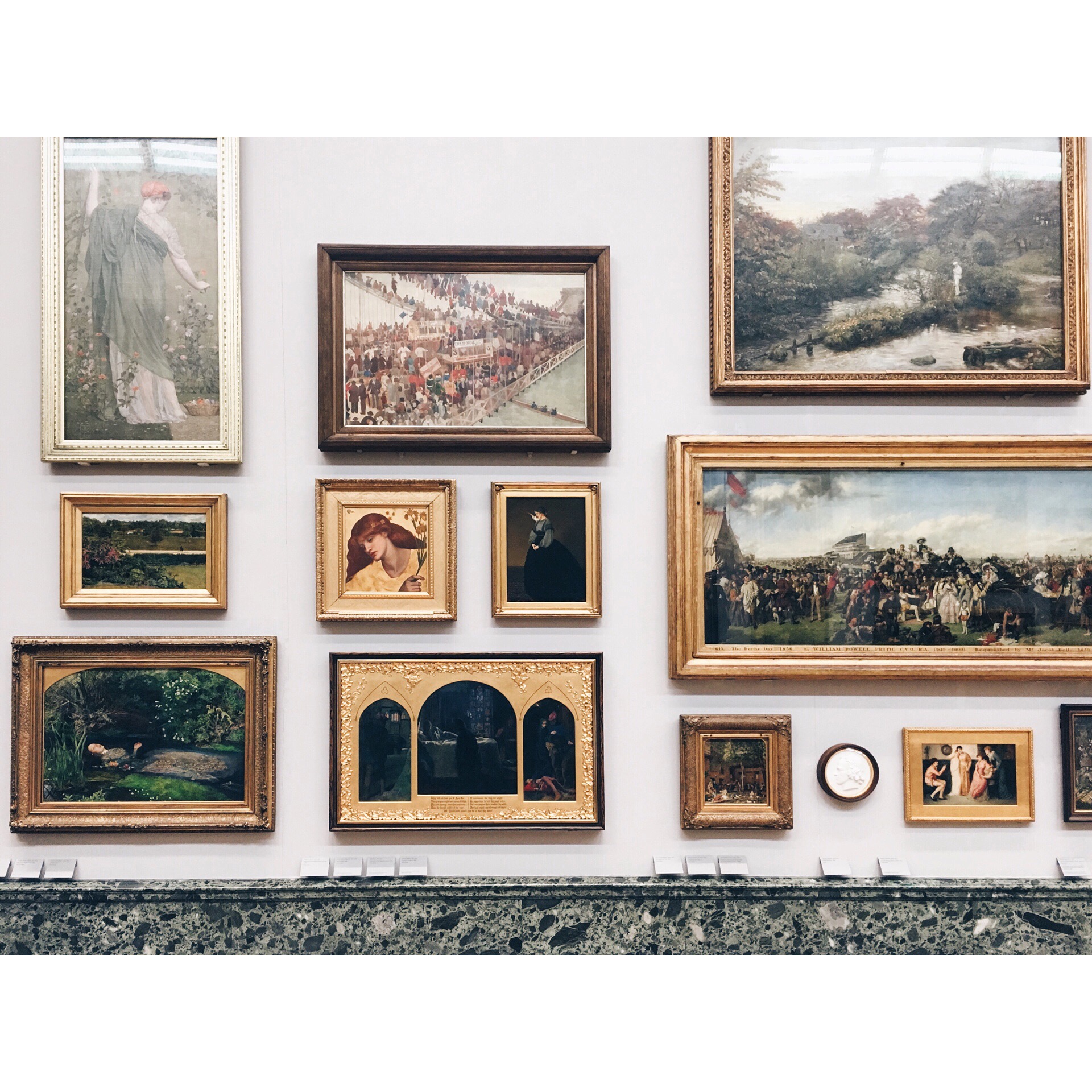

London, and the UK, certainly have some of the best galleries, museums, permanent collections and exhibitions that the world has to offer. Whether you want to examine the finest, pre-Raphaelite Waterhouse painting or sample the curvatures of a Henry Moore sculpture, it’s here. However, in recent years, I have noted that my decision to visit the art houses of the country has been increasingly dependant on connecting to the space in which the pieces are housed, as opposed to the objects themselves.

My fascination with the gallery as an architectural curiosity began at London’s Tate Britain. On a grey, dismal September Saturday, I set out to walk along the embankment towards parliament. I was keen to take in the sights, but Big Ben and the London Eye were so familiar and engrained in my mind that I didn’t feel the need to stand and gawp at them as many other tourists were doing. And rightly so, they’re beyond iconic and impressive. Instead, I continued away from the hoards and found myself heading towards Pimlico where i was shortly confronted by the Tate Britain. I entered.

I was astounded by the towering structure in which I had been engulfed. The gallery has cavernous hallways, display rooms with ceiling heights to rival any atrium and neo-classical strength in its construction that separates the outside world from the treasures inside. The dull and glib sound of persons slowly wandering through the space is oddly comforting and with this I find myself returning to these places not to gaze at the Turner oil-on-canvas, but rather just to be there.

It is this security and purpose to protect that is echoed amongst its counterparts across the UK’s capital, and indeed in many of the galleries and museums across the country. The familiarity of the dusty scent, mixed with artisan coffee brewing in the conditioned and compulsory cafés now attached to these attractions is beyond comforting.

The grandiose exteriors suggest the importance of the objects it houses and yet provides sanctuary with permanence beyond even the oldest relic on display. The buildings are designed just as much for the ‘things’ as well as the people looking at those ‘things’.

Take Oxford’s Museum of Natural History. It has curiosities from around the world stuffed and packed into its halls and hanging galleries. Natural, cultural and social history is pouring from animal skeletons and Native American artefacts, but still I am admiring the neo-classical design, wooden floors, repeating cast-iron pillars and vast glass roof. My childhood counterpart would have stared for hours at a stuffed lion and the Egyptian mummies, imagining how these items were plucked from lands so far and peripheral to my life.

Most recently, my wanderings took me to the Horniman Museum, in South London. Sitting beyond Dulwich and on the edge of Forest Hill, this is surely one of London’s museum gems. A mass of Victorian architecture, standing like a fort aloft a hill, the museum oozes intrigue and a stateliness that could rival any of the colossal structures on Exhibition Road. On entering, my eyes soared to the bowed ceiling. I then continued to sit and absorb the space until a friendly tour guide asked if I was quite alright some twenty minutes. I assured her that I was more than happy.

In contradiction to the monolithic galleries of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the stark and ultra-modern ‘Hepworth’ museum in Wakefield, Yorkshire could appear cold and too minimalist to enjoy the space as a nurturing environment. However, its solid and angular formation is softened by floor to ceiling windows that invite the warm, natural light to filter through. Not only does this negate the overly clinical whitewash walls, it also allows the space to breath and as it does, so do you with it.

I am always hesitant to leave the spaces and return to the moving world outside.

Alluring, tactile, enticing and familiar. All words attributable to the galleries I have visited. Perhaps it is the old ‘if these walls could talk’ idiom that plays true here, and perhaps I just simply enjoy the beauty and thought put into the design of these buildings. But I urge you to look beyond the items and admire the space in which they are being studied. It’s worth it.

Tate Britain: Millbank, London SW1P 4RG

Oxford Museum of Natural History: Parks Rd, Oxford OX1 3PW

Horniman: 100 London Rd, London SE23 3PQ

Hepworth Wakefield: Gallery Walk, Wakefield WF1 5AW