On February 12, 2012, the feminist punk rock band Pussy Riot broke into an impromptu concert at the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow. For a few minutes, before being dragged out by security, the women managed to make their case: “Holy Mother, Blessed Virgin, chase Putin out!” The stunt caused a stir online, but became an international sensation when three of the band’s members were charged with hooliganism.

One of the girls, Yekaterina Samutsevich, was given a suspended sentence, while Nadezhda Tolokonnikova and Maria Alyokhina were convicted and sent to detention centres in Mordovia and Perm, respectively.

Artists and human rights activists all over the world protested the decision, claiming it was an example of Russia’s crackdown on freedom of speech. Tolokonnikova and Alyokhina were released in December 2013, but they have since continued to appear under the media spotlight.

At the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics, they were beaten by Cossack security guards during one of their flash recitals, and in March they were assaulted by men in civilian clothing at a McDonald’s in the city of Nizhny Novgorod.

As famous as the exploits of Pussy Riot have been, however, they are an off-shoot of the art collective, Voina. In many ways, this longer-established movement is even more radical and notorious. It was founded in 2006 by Oleg Vorotnikov and his wife Natalia Sokol. Tolokonnikova and her husband, Pyotr Verzilov, were also among the founding members, although they would eventually break with the group in 2009.

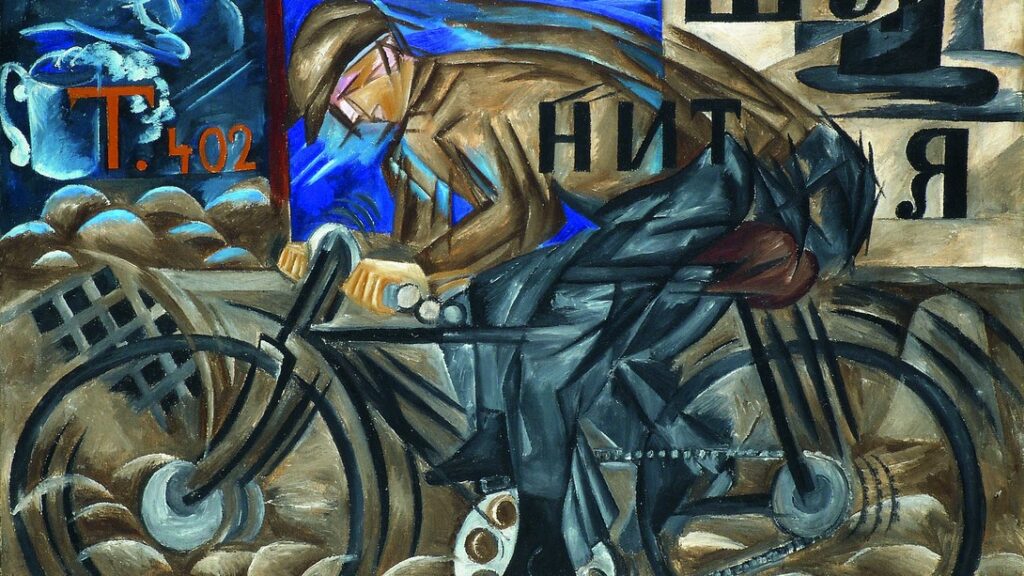

Other activists involved with Voina include: Alexei Plutser-Sarno, the group’s spokesman and ideologist; photographer Yana Sarna and Leonid Nikolayev, its president. Like Pussy Riot, Voina are products of the Internet age. Their actions are local and relatively small-scale, but through the Web, their message has been heard around the globe. As they’ve admitted to Anarchist News, their goal is to revive left-wing art in a context in which, as Sokol suggests, “there is no other radical art in Russia.” Plutser-Sarno added in the same interview that: “painting flowers and pussy cats or making any other ‘pure’ art, lacking a socio-political content, is to support the right-wing authorities.”

According to the members of Voina, disruptive activism is the only kind of politically-engaged art still possible in their country, where, says Nikolayev, “xenophobia and homophobia reigns, a new slave society is being built, and cops beat and kill people”. The group introduced themselves in early 2007, throwing live cats at employees in a McDonald’s in Moscow, chanting: “Death to fast food!” and “No to global fascism!”

Their first major act came later that year. They had planned to stage a performance with the poet Dmitri Prigov, whom Voina consider an inspiration, but the artist suffered an untimely death. In his memory the group organised an unusual funeral wake inside a Moscow subway train, installing a table in the middle of a carriage and enjoying drinks and food. Once the reunion was over, they left behind all their leftovers, so that “they would circle for all eternity”. Pictures and videos of these actions circulated around the Web, thanks to blogs and YouTube.

In 2008, in the lead-up to the presidential elections, Voina held a scandalous public orgy in the National Biological Museum. The prank was a reference to Dmitry Medvedev, the Putin-backed candidate who would go on to win and who had called on Russians to raise their country’s birth-rate.

Voina satirised his remark by copulating for “Baby Bear’s heir,” a pun on the soon-to-be president’s name: “medved”, which means “bear” in Russian. The incendiary video exploded on the Internet and put the group on the artistic map.

Voina would go on stirring controversy in ensuing months and years. Never receiving support from government bodies or galleries, its members embraced a penniless lifestyle and scorned money. To nourish themselves they would steal from supermarkets, where they would also stage many of their acts. In one example, an activist walked away with a trolley of products in plain sight, disguised as a cross between a Cossack and an Orthodox Christian priest. Voina meant to test whether or not a representative of such untouchable institutions could get away with shoplifting. As it turned out, this was indeed the case. In another supermarket, also in 2008, Voina pretended to conduct a public hanging of three Asian migrant labourers and two gay men. Again, they targeted Russian authorities, specifically Yuri Luzhkov, the then mayor of Moscow, known for his racist and homophobic policies.

Arguably, their two masterpieces came in 2010. In June, on a St. Petersburg drawbridge, Voina spray-painted a gigantic phallus. When raised the inflammatory artwork faced the headquarters of the Federal Security Agency, the successors of the KGB. Despite its obviously controversial nature, this piece surprisingly won a prize for innovation from the Russian State Center for Contemporary Art.

Voina’s following venture, however, would inspire a far harsher official reaction. In a performance entitled “Palace Revolution”, the group’s members overturned a police car in St. Petersburg.

They filmed the stunt and uploaded it to YouTube. The video includes a cheeky prelude, in which Vorotnikov’s son loses his ball under the ill-fated car, which is then turned over to retrieve the toy. Of course, there was a larger message: the police needs to be flipped upside down and be thoroughly reformed. The authorities disagreed.

In November 2010, Vorotnikov and Nikolayev were detained and charged with hooliganism and organising a criminal organisation. According to Voina, in an interview with Art Threat, the arrests were carried out without a search warrant and both activists sustained injuries and hematomas due to police mistreatment. Famously, British graffiti legend Banksy raised more than $130,000 to bail them out, but the Voina members languished in jail awaiting trial until March 2011, when Vorotnikov and Nikolayev were finally released. Vorotnikov then skipped bail and went into hiding with Sokol and his child.

Voina has continued to operate, but in a lesser capacity. In 2009, a rift opened within the group when Tolokonnikova and Verzilov were accused by the other members of informing on a fellow activist from the Ukraine. Verzilov denies the claim and suggests that Voina ruptured into different Moscow and St. Petersburg factions, though Sokol, Vorotnikov, Plutser-Sarno, Sarna, and Nikolayev insist that no alternative faction exists.

Whatever the case, and despite animosity towards Verzilov’s wife Tolokonnikova, in a 2013 interview with The Quietus, Sarna confirmed that Voina and Pussy Riot were allies.

More recently, in May 2014, Vorotnikov expressed support for Russia’s annexation of Crimea, announcing that Voina would not participate in the Dutch OpenBorder festival, whose organisers had been critical of Russia’s actions. Although the group has suffered internal dispute and official persecution, it’s still a symbol of radical expression in Russia. Their aesthetic and frequent disruptions of public space, however, are not always popular, and many locals do not support or understand them. Those who identify with the political and moral codes lampooned by Voina tend to find them unacceptably offensive. It remains to be seen whether or not such radical groups inspire change or if they will remain anecdotes in a cultural conversation largely hostile to their brand of activism.