Despite its depth and richness, Argentine cinema is not as well-known as it could be. The centres of film discussion, historically, have been located in Europe and North America, and the South American nation – along with many others in Asia and Africa – has played a mostly marginal role. Worse still, the preservation and restoration of its cinematic heritage continues to be an ongoing battle, and even local cinephiles struggle to find watchable copies of their country’s old movies.

Yet the situation is changing, as an increasingly international film culture, bolstered by the internet, discovers what it has been missing in previous decades. In this spirit, we will highlight the work of three noteworthy Argentine directors who, though far from obscure, deserve more exposure.

1

Leonardo Favio

Leonardo Favio is likely the nation’s most revered filmmaker. Yet, he is a relative unknown to the rest of the world, even in Latin America he is largely remembered as a singer, a career he only embarked upon to finance his movie projects. However, for countless directors in Argentina, he has been massively influential. He started as an actor in the 1950s, but he eventually stepped behind the camera and began to create a stream of masterpieces. His breakout came in 1965, with Chronicle of a Boy Alone, about a low-class teenager who slides between reform school and a slum, never managing to escape the jaws of his context. Favio’s trademarks were already present: his sensibility for social problems, his skill for striking compositions, and his use of dead time and silence. He would expand on these themes in his two subsequent classics, The Romance of Aniceto and Francisca (1967) and The Dependent (1969).

During the 1970s, Favio reinvented himself: convinced that his earlier movies were too arty and elitist, he adopted a wild and operatic style for Juan Moreira (1973) and Nazareno Cruz and the Wolf (1975), inspired by contemporary music videos and pop imagery. Both movies are explosions of colour, camera movements, and extravagant drama. Favio would continue going down this artistic alley, with his mythic boxing epic Gatica, el mono (1993) and Aniceto (2008). The latter was his final work and a fitting encore: after decades of making characters move around cinematic space like dancers, Favio went ahead and filmed Aniceto as a ballet on a theatrical stage.

2

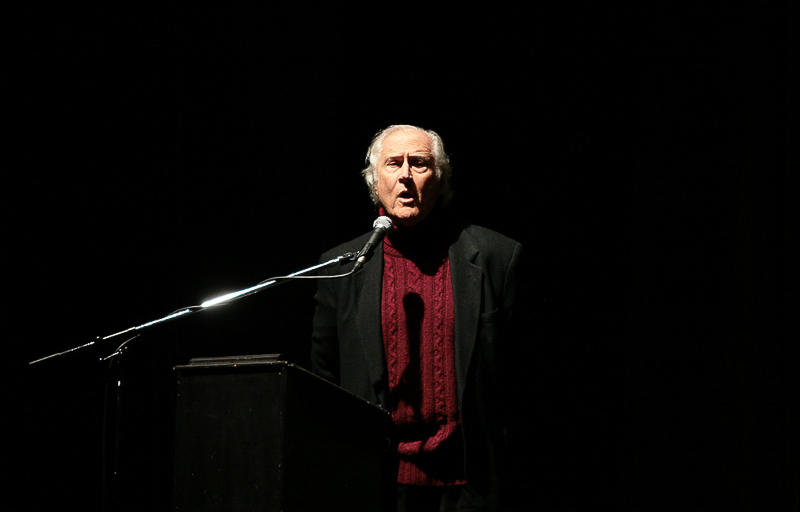

Fernando Solanas

Fernando “Pino” Solanas broke into the scene with The Hour of the Furnaces (1968), an incendiary documentary about, among other things, the exploitation of the working masses by an Argentine high class led by pernicious foreign influences. Discarding subtlety or objectivity, it bombards viewers with hyperkinetic editing, didactic on-screen text, and frantic juxtapositions. It was predictably outlawed in Argentina, then under military rule, and praised abroad at international festivals, coming to represent the brand of activist film-making Solanas hoped to spur when, with Octavio Getino, he founded the Liberation Cinema group in 1969. Alas, the violent 1970s forced Solanas to flee to Europe, and he returned to Argentina when democracy returned in the 1980s. His movies from this later period are markedly different from The Hour of the Furnaces. Ditching the use of rapidly cut documentary and stock footage, he began crafting contemplative and surreal fictions, like South (1988) and Gardel’s Exile (1986), about artists dealing with personal and national identity amidst political turmoil and dictatorship. Since then, Solanas has gone back to capturing Argentina’s present through documentaries.

3

Lucrecia Martel

Lucrecia Martel is also a political artist, if not as overt. She tends to look at how social, sexual, and economic divisions cut into the domestic sphere. Her middle class families – in The Swamp (2001), The Holy Girl (2004), and The Headless Woman (2008) – suffer the twin traumas of aimlessness and generational rifts. Children and teenagers are alienated from their parents, who are often listless and drunk, and the adults are sometimes alienated from themselves: if a horrible accident disturbs their complacent existence, their perception of reality can be thrown out of order. Martel is one of the main figures in what, during the late 1990s, came to be labelled New Argentine Cinema. Although it has no specific program nor consistency among its members, this movement is roughly characterised by youthful directorial voices and an emphasis on everyday life. Yet the apparent realism of some of these works can be deceptive. Martel, in The Headless Woman, allows the subjective paranoia of her protagonist to twist the objective world without in small and almost imperceptible ways. Her next project, still unreleased, might follow the same tantalising path: an adaptation of Antonio di Benedetto’s novel Zama, famous for capturing the feverish mind of an 18th century Spanish civil servant in Latin America, through the protagonist’s own highly unreliable first person narration.

Favio was the brightest cinematic flame during Argentina’s effervescent 1960s; Solanas managed to capture, through his works, the political transformations of the 1970s and 80s; and Martel is a perfect example of the current moment, in which many filmmakers, without a shared ideology, are developing their artistic sensibilities in a changing worldwide film market. But they’re only the beginning for the adventurous cinephile.